ESSAYS

WANJERI GAKURU

BICYCLE STORIES

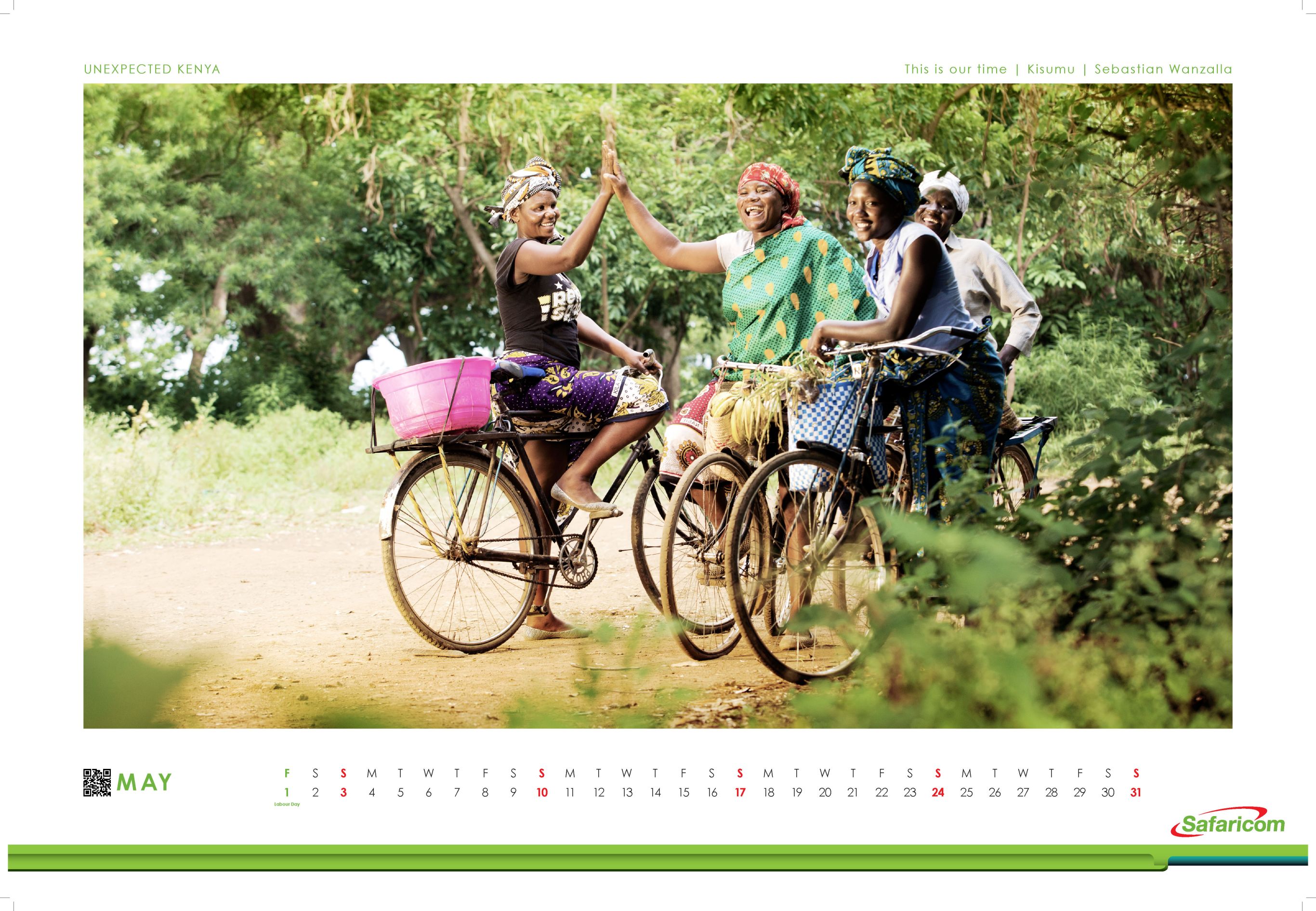

This is our time, Sebastian Wanzalla, 2017.

Through a thicket, you see four women perched on bicycles, laughing and high fiving each other. Their lessos are colour coordinated, and woven baskets laden with produce dangle off the handlebars. It is a produced moment, warm and bright, perfect for inclusion into a calendar and a coffee table book. But away from the camera’s gaze, the women speak of less joyful things, of being anomalies, the subject of jeers and insults. It is 2014 and I am out on assignment to capture “unexpected Kenya”. The high fiving women are cyclists from the port city of Kisumu, selected from an eclectic group of eight. They are in their early 30s to late 50s, a mix of entrepreneurs and homemakers alike. Although cycling increases their mobility, not everyone sees it that way. The women all speak of being accused of "spoiling men's food" by cycling.

Doin’ work. A woman in Nzega, Tanzania, rides her bicycle as she goes about her business,

Wanjeri Gakuru. 2017.

Wanjeri Gakuru. 2017.

Kenyan scholar, Professor Wambui Mwangi, prefaces her New Inquiry essay, Silence is a woman with a quote from Gikuyu architecture: “The general term for a woman is ‘mutumia,’ meaning ‘one whose lips are sealed.’”1 In East Africa, like everywhere else, the female body is often a target for male domination and censorship. Yet throughout history, Professor Mwangi points out, women have always found ways of turning their bodies into weapons of subversion. “Women’s power deployed in this way can only be oppositional, always a challenge, always-already embodying and performing the power to refuse.”2

To cycle is to be highly visible. It is to be vulnerable to the elements. Yet to cycle is also to trust in oneself and be propelled forward by muscle and sheer willpower. In this context, the image of a woman cycling is oppositional, always a challenge, always-already embodying and performing the power to refuse.

—

It is 2013. Kisumu county assembly member Caroline Owen tries to pass a by-law banning women from riding bicycles and motorcycles sideways. Absurd as it sounds, she gains support. The act of sitting with legs astride on two-wheeled transport is “demeaning,” she says, “uncultural.”3 “‘Legs Together’ Law to Uphold Culture for Kenya’s Female Bike Riders,’” reads one headline. Scrolling through the comments section beneath the news clip on YouTube, a commenter writes: “And how are they supposed to ride the motorcycle again? Or are they always just going to be passengers?”4

Lady red. A young headscarfed woman cycles past a furniture seller in Nzega, Tanzania,

Wanjeri Gakuru, 2017.

Wanjeri Gakuru, 2017.

In recent years, bicycle access programmes have donated two-wheelers in their thousands to communities across Africa with marked increases not just in education quality but employment opportunities, reproductive health, and property rights. Wheels of Change, a 2017-2018 report on the impact of bicycle access in rural Zambia, found that giving girls access to bicycles reduced their absence from school by 28%: “The program also improved measures of empowerment, including girls’ sense of control over the decisions affecting their lives i.e., their “locus of control” increased.”5

—

“The earliest bicycles in Kenya were used by the unholy tripartite of colonial conquest: administrators, missionaries, and settlers,”6 writes Kenyan journalist and archivist, Owaahh in his essay, ‘Nita Ride Boda Boda’ for The Elephant. By 1930, bicycles had grown in popularity, but they remained accessible only to working-class men. The women who managed to ride bicycles did so because they came from families that already owned one. Reliant on their patriarch’s benevolence, Owaahh notes that a good number of stories of the first women to get an education involved a bicycle, often of a father carrying his daughter to school.

—

2017. I am travelling across the Greater East Africa, with a mobile literary and arts festival, when I notice something peculiar, a rural town in Tanzania where women cyclists abound. The numbers are astonishing. The place is called Nzega, and the women wear dresses and lessos and buibuis as they ride. Some have water jerricans strapped to their bicycles and others have babies on their backs. It is the casualness that strikes me, and I feel an immediate kinship with these women, a kinship that stretches back to a similar encounter in Kisumu three years earlier.

The women of Nzega inspire me to purchase my first ever bicycle. I track down a seller in the town and out of rows and rows and rows of beautiful second-hand Japanese imports I find my stunning beauty and name her after the town. And years later, when a global pandemic narrows our lives, I will take to cycling in the estate parking lot in the small hours of the morning. Lanes then emptied of children and their anxious guardians, music blasting in my ears and the night sky up above, I will feel freedom.

All oppression is connected.

All freedom is connected.

— Staceyann Chin

Catch me if you can. A woman adorned in a lesso powers down the streets of Nzega, Tanzania,

Wanjeri Gakuru, 2017.

Wanjeri Gakuru, 2017.

In his essay, Owaahh references a newspaper advert in Mambo Leo, a local language daily, placed by the British bicycle manufacturer, Raleigh, in June 1930. The Raleigh bicycles were known colloquially as “Black Mambas” or “Blackies”. To this day, Raleigh remains popular among blue-collar workers and is a staple in lower income households across East Africa. It is what the women in Kisumu rode. And yet, when high-level conversations regarding road infrastructure, alternative modes of transport or green energy take place, the dominant image in the heads of town planners is that of an elite cyclist—here it could be male or female—who owns a roadster worth tens of thousands and can be seen whizzing past in the ‘appropriate’ apparel, cycling shorts and glasses, reflector jackets and helmets. There is a hierarchy regarding whose cycling body matters.

Despite my Nzega’s history, I am an urban cyclist myself, part of a troubling narrative that ought to change. Professor Mwangi writes of ‘Wanjiku’, an iconic representation of the ordinary Kenyan citizen whose name never appears in news broadcasts or newspaper pages. And as I scroll through the websites with smiling faces of happy bicycle recipients and urban planning panels stuffed with engineers and architects, I think of Professor Mwangi’s description of Wanjiku as “the voice of those who are subject to the actions of the powerful but never powerful themselves.”7

—

I write about the everyday cyclists and the beauty I see in them because they matter. There is a great measure of speculation involved in all this, I know. I didn’t interview the Nzega women, for instance, and my desire to ascribe special meaning to their lives perhaps unfairly demands that they tell some larger story than simply being who they are. What I know for sure, however, is that everything I saw and felt in Nzega and Kisumu mirrors how friends in Amsterdam and Berlin interact with their bicycles. I can see clearly that a bicycle can and does represent everything I want for myself and women everywhere: freedom, autonomy, and fluidity.

1. Wambui Mwangi, ‘Silence is a Woman’, The New Inquiry, (June 4, 2013). The full text of the essay is available here: Silence Is a Woman – The New Inquiry

2. Ibid

3. The KTN News Kenya insert featuring Kisumu county assembly member, Caroline Owen, is available on YouTube as ‘Kisumu Boda Boda Motion Targeting Women Riders’ and can be viewed here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZI8D4HCfsVA 4. ibid

5. In rural Zambia, researchers partnered with World Bicycle Relief to evaluate the impact of bicycle access on girls’ educational and empowerment outcomes. The findings of that study, ‘Wheels of Change: The Impact of Bicycle Access on Girls’ Education and Empowerment Outcomes in Rural Zambia,’ are available here: https://www.poverty-action.org/study/wheels-change-impact-bicycle-access-girls%E2%80%99-education-and-empowerment-outcomes-rural-zambia

6. Owaahh, ‘‘Nita Ride Boda Boda’: How the Bicycle Shaped Kenya’, The Elephant, (March 28, 2019). The full text of the article is available here: https://www.theelephant.info/culture/2019/03/28/nita-ride-boda-boda-how-the-bicycle-shaped-kenya/

7. Wambui Mwangi, ‘Silence is a Woman’, The New Inquiry, (June 4, 2013).

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Wanjeri Gakuru is a journalist, essayist, and filmmaker. A cross-section of her writing has appeared in Transition Magazine, The Africa Report, The Elephant, LA Times Magazine and CNN, among others. She was selected the 2018 Literary Ambassador for Nairobi by Panorama: The Journal of Intelligent Travel and in 2020 appointed Nataal’s Nairobi-based Contributing Editor. Gakuru is the Board Secretary of Jalada Africa, a Pan-African writers collective. Gakuru was appointed to this role at the completion of her two-year term as Managing Editor of the Collective. She is also a founding member and the Partnerships Director of Rogue Film Society (RFS), a collective of multi-talented African filmmakers and thespians working in film, TV, theatre, and advertising.